23 Jun Blog: Complex calenders

By Kathy Wellen

21 June 2017 marks the first day of summer in the northern hemisphere. Dutch children still have to wait a few more weeks before their summer vacation starts, but in astronomical terms, summer officially arrives Wednesday. The difference in between school calendars and the sidereal calendar is minimal in countries where the Gregorian calendar is accorded paramount importance thus we are inclined to forget that there are many other calendars in the world. One of these is the Muslim calendar which is 354 or 355 days long. As a result, Muslim holidays travel through the year. As a result Eid ul-Fitr will be celebrated next week at the height of summer whereas twenty years ago it was celebrated during February.

With the demise of spring, there are few tulips to be seen in the flower fields of the Netherlands, but people travelling to Bali will see flowers everywhere. Not just growing in gardens or in a vase on a table, but also on the roadside, in temples, at trailheads, on stoves or next to motorbikes. While they appear ubiquitous, there is actually a method to their placement, and this method relates to calendars.

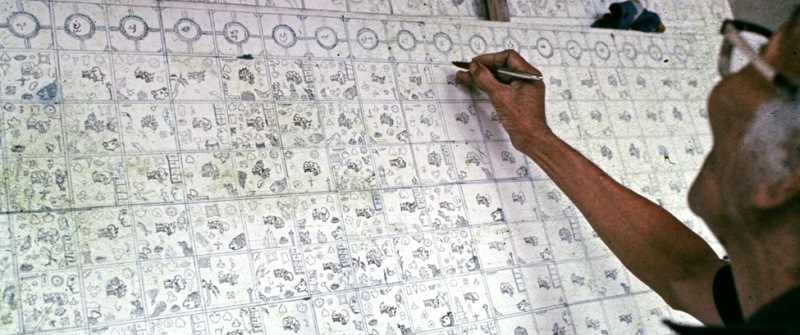

There are numerous calendars in use on Bali. These include the Balinese calendars known as Pawukon and Saka as well as the Muslim, Chinese and Gregorian calendars. The Pawukon calendar consists of 210 days divided into ten different weeks. The weeks vary in length ranging from ten days to one day, which Clifford Geertz calls “the ultimate of a contemporized view of time”. Because these ten weeks run concurrently, any given day can have ten different names.

The Saka calendar is based on Indian astronomical traditions. The discrepancy between the lunar and solar years is accommodated by assigning two lunar days to one solar day every 63 days. This still leaves a 9 – 11 day deviation from the solar year which is accommodated by the insertion of a intercalary or leap month known as saseh nampeh every thirty months. The Pawukon calendar is considered more important. It is used to determine good days for travelling, starting a business, harvesting crops, planning a wedding or constructing a house. When certain days of the various weeks in the Pawukon calendar intersect, these days are also considered to be auspicious. An example is Kajeng Kliwon which occurs every fifteen days when the day Kajeng of the three-day week and the day Kliwon of the five-day week intersect. Honoring Siva, one of the principal Hindu deities, Kajeng Kliwon is used for purification and for prayers that the negative forces in the world do not overpower the positive ones. Many Balinese mark the occasion by consulting a priest, visiting a temple or by making offerings. Flowers are popular offerings but offerings can also consist of multi-colored rice known as segehan or a kind of liquor known as tetabuhan arak berem. It is also a day when many Balinese are inclined to stay home so as to avoid bad fortune. Kajeng Keliwon occurred last week on June 14 and it will occur again next week on June 29. These intersections can be viewed on a traditional calendar or an on-line calendar.

Used more for pinpointing certain days than for measuring time, the Pawukon calendar may seem esoteric, but it remains relevant in the modern world. Through observing rituals determined by this calendar, the Balinese reaffirm their commitment to their traditions and their community. The Pawukon calendar also plays an important role in the agricultural cycle. With its weeks of varying lengths, it can be used to keep track of different, simultaneous intervals useful to coordinate irrigation schedules and synchronize production cycles which are essential to traditional rice agriculture in Bali. J. Stephen Lansing studied the manner in which Balinese calendars and water temples play an important role the production of rice, as well as the problems that ensued when proponents of modern agriculture insisted that Balinese farmers abandon their traditional methods.

(Kathryn Wellen is a historian of Southeast Asia specialized in the early modern era. Her current research project is a statistical analysis of marriage, military conquest and state formation among the Bugis in the Cenrana Valley in South Sulawesi).

No Comments