05 Dec Blog: Contesting the Sinterklaas tradition, mediating belonging, defining Dutchness

By Joeri Arion

The first month of what seems to be the longest season of the year evokes warm associations with tradition, homeliness and joy: Gezelligheid. Simultaneously, early December also comes with a sensation of estrangement; a certain ambiguity of my sense of belonging.

December has the fewest daylight hours, making it the darkest month of the northern hemisphere. But, as hemispheric ‘northerners’ and cultural beings, we excel in lightening up this dark time with an abundance of meaning and animation. The ostensibly joyful, but nowadays much contested Sinterklaas celebration is one of the most obvious examples of this.

Dissonance

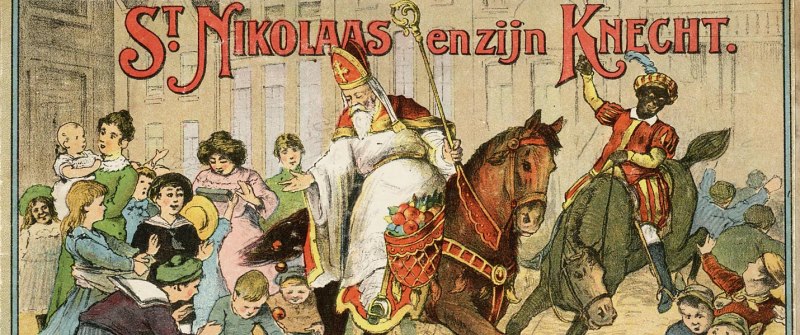

During the second wave of European colonialism, about three years before the KITLV was founded, a school teacher residing in the inner city of Amsterdam drew a picture book with an unimaginably powerful impact. It was this book – Sint Nicolaas en zijn knecht, published in 1850 – that gave birth to the dissonant caricature of ‘Black Pete’ (Zwarte Piet); the clownesque servant (knecht) of his master Saint Nicholas. This version of an existing narrative gave rise to the invented tradition of het Sinterklaasfeest as it is celebrated today; a tradition that has become intangible cultural heritage. By virtue of being Dutch cultural heritage, the Sinterklaas celebration is enjoyed annually in the form of cultural performances, folkloristic songs, tales, and theatrical events.

Despite the communion it creates, het Sinterklaasfeest is increasingly contested along the axes of identity and belonging; an inevitability of its dissonant character. Sinterklaas creates a strong sense of belonging among the communities identifying with it. At the same time, as is the case with all cultural heritage, it embeds the personality of a group and forms ‘constructs of belonging’. By this token, the tradition also invariably affects the exclusion of Others.

Caribbean Diaspora

Not everyone participates in the joys of Sinterklaas. I spent a large part of my childhood in the Bijlmermeer; a borough situated on the south-eastern margins of Amsterdam, which from the 1970s to 1990s was home to a Caribbean diaspora as its largest demographic. Growing up in such a locality in the late 1980s and early 1990s, I can’t remember ever seeing Sinterklaas or his servants showing up in my neighborhood. When I turned to my mother for clarification, she told me that Sinterklaas lacked the resources to deliver gifts in the honeycomb projects of the Bijlmer. ‘We have no chimney through which he can enter our house’, I must have thought. I later realized that our family did not celebrate Sinterklaas because of the colonially rooted portrayal of Black Pete, a racist caricature. ‘Obviously a caricature’, many progressives exclaim these days. Not so much back then. In all my childhood naivety, the way Pete was play-acted by white Dutch folks – with Surinamese and/or Antillean accents, frizzy wigs, and ‘blackened’ faces – was a source of uncertainty and confusion. I didn’t understand why it was condoned and nationally encouraged to stereotype and ridicule a set of characteristics that even my young self immediately associated with Caribbean people. In hindsight, I came to realize that our resistance back home to participating in this cultural heritage constituted a form of silent protest.

Heritage is conceptualized and selected through a cultural lens, and ultimately constructed by those in power. In our multiform and ever changing society, heritage is no exception in being constantly subjected to the forces of change. Will such change, and the dynamics in which it is embedded, facilitate inclusivity? Will it strengthen the Dutch community?

Resolution

It’s been six years this December since seemingly silent protests started to change the dominant discourse surrounding Sinterklaas. Since that moment, peripheral perspectives have managed to gradually alter what was once thought of as unbreakable cultural hegemony. Unfortunately, the turmoil in Dokkum seen at this year’s Sinterklaas celebration has laid bare a brand of fanaticism that leaves no room for such fragile, subaltern perspectives on Dutchness. Whenever December comes around, I’m starkly reminded of the precarious and competitive space in which “being Dutch” continues to be defined.

Photo: J. Vlieger, Amsterdam.

(Joeri Arion is a PhD candidate in the Traveling Caribbean Heritage project. Within this research project, his role will mainly focus on raising insights and seeking clarity in the conceptualization of cultural heritage in the context of nation-building practices in the Dutch Caribbean and in the Netherlands in the ‘post-Netherlands Antilles’ era.)

No Comments