27 Nov Blog: Tales of war’s boredom: The spy who loved flowers

While the recent academic, public and legal attention for the decolonization of Indonesia rightly focuses on violence as one of its defining characteristics, we should not lose sight of the other aspects of the conflict. Christiaan Harinck takes a look at some of these aspects, including boredom and a alleged spy who dealt in flowers.

War is boring?

Indonesia’s war of decolonization was a bloody conflict. But while the war was bloody, often it was also very boring. Except for those in the most hotly contested area’s, most people did not encounter violence on a daily basis. This rings true not only for civilians, but also for soldiers and irregular fighters. Even in wartime, where the threat of violence is often near, actual moments of violence are the exception. This is aptly reflected in most of the published memoires and diaries of Dutch veterans. Most of these books pay more attention to friendship, the journey by sea to Indonesia, scenic trips and sports games, than to actual violence and sharp encounters with the enemy.

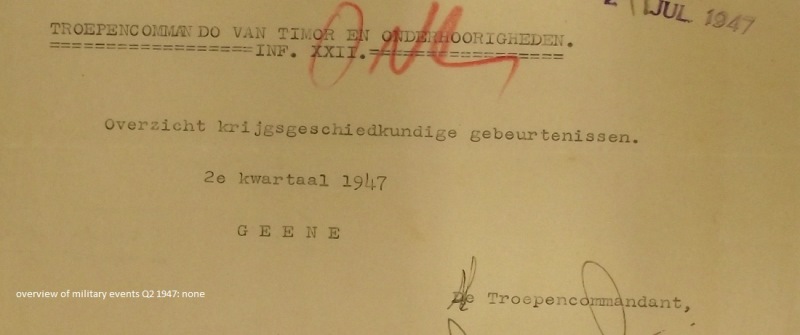

As military reports usually only deal with military matters, the war’s other aspects are often only found ‘between the lines’. But sometimes it is quite explicit. Take for example the commander of the Timor garrison. His reports back to the army high command in Batavia were so sparse (‘overview of military events: none’) that he had to be ordered to write more elaborately in 1947. However, the problem was not that the commander was unwilling. Most of the time, Timor actually was very tranquil.

Fishy flowers

To give a second example of war’s tranquility, we’ll take a look at Borneo (present day Kalimantan), another backwater, in 1948. By early 1948, the North-Eastern part of the island had been largely pacified. Dutch soldiers still went on patrol, but only to show off the Dutch might. The military authorities in Balikpapan were not idle, however. Enemy infiltration was to be anticipated. And so it came that a certain mr. Achmed Palembang aroused the suspicion of the authorities. Mr. Palembang, a ‘rather sinister person’, stood in close contact with known local Republican leaders. Achmed had a florist shop in Balikpapan. But because he made very little money and he often traveled to Java, the authorities considered his shop to be a cover for illegal activities. Besides, the origins of his flowers were unclear and suspicious, as were his contacts in Surabaya. Justified as the military’s suspicion might be, this spy who loved flowers was the most exiting case in a six month period.

Symposium

These two examples might illustrate some of the other aspects of this colonial war that, depending on time and place, was both bloody and boring. Currently, several KITLV researchers and interns are working in the National Archives in the Hague on military and governmental archives relating to the war in Indonesia 1945-1950. Our focus is on violence, and more. Please join us on December 3th at the first symposium on our findings so far in the National Archives.

No Comments