25 Feb Blog: The Mystery of the Missing Mammary

‘The Mystery of the Missing Mammary: Musings on Mutilations as Meaningful Memories’. One-Tété Lohkay in St. Maarten, Alida in Suriname – the legend of the enslaved woman whose breast was cut off by a cruel master or mistress occurs not just in the former Dutch colonies but also in many other post-slavery societies of the Americas. These women have become folk heroines. What to do, though, asks Jessica Roitman, as an historian who wonders if these brutal disfigurements actually occurred? Or what to do if some of these women never existed at all?

Legendary Lives

The story goes that a young woman named Lohkay was enslaved on a plantation in Dutch St. Maarten. She rebelled and ran away. Lohkay was hunted down, recaptured and brought back to the plantation. As punishment for her defiance and as a warning to other slaves, the master of the plantation ordered that one of Lohkay’s breasts be cut off and, hence, she became known as One-Tété Lohkay.

Despite this mutilation, she was saved by local plants and supposedly grew even more courageous and determined to liberate herself. Lohkay escaped again and lived alone in the hills, occasionally coming down to raid plantations for supplies. The legends say that slaves heading out to the fields in the early morning could see the smoke from Lohkay’s camp in the hills .

The story of Lohkay is similar to that of Alida in Suriname. Most stories about Alida agree that her mistress, Susanna du Plessis, was upset by her husband’s interest in the young woman. In a jealous rage, she mutilated Alida by cutting off one of her breasts. It is not clear what happened to Alida after her mutilation.

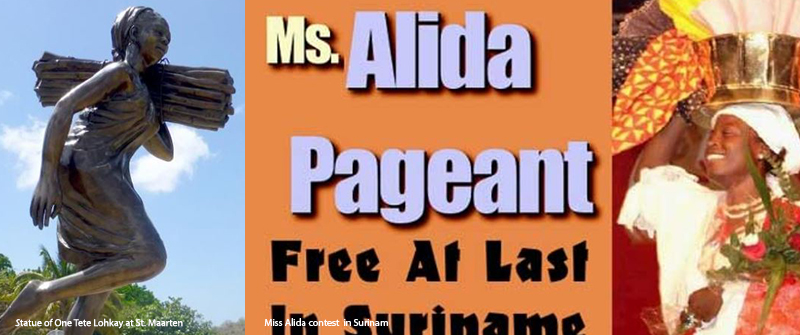

Alida, like Lohkay, has become a national symbol, particularly for young Afro-Surinamese women. There is an annual ‘Miss Alida’ contest in which the contestants are judged not on their physical appearance but, rather, on their awareness of their cultural background and their ambition to further themselves. And in 2006 the people of St. Maarten unveiled a statue of Lohkay.

Verification, Vindication, and Viewpoint

For historians it is hard to judge the veracity of these tales of female courage, victimization and defiance. It is nearly impossible to ascertain if these mutilations occurred. More troubling still is the difficulty in establishing if these women were real historical personages.

For instance, it is not possible via the written sources to link Susanna du Plessis with the possibly fictional Alida. In-depth research by Hilde Neus-Van der Putten (2003) has shown the reality was more complicated. According to Neus-Van der Putten, claims of du Plessis’ cruelty were exaggerated and originated in the threat perceived by white male planters when faced with financially independent white women.

Likewise, the archives of former slave societies give a relatively complete picture of the sorts of punishments meted out to the enslaved population. There is rich documentation available for the legal systems within these societies, including countless court cases involving the (mis)treatment of enslaved people . None of these sources show that the mutilation of a mammary ever occurred.

Every former colony seems to have exactly one story of a brave woman whose breast is cut off – and never more than that one. If this type of mutilation was really a fact of life, it would have been expected that it not only would have been mentioned in the archives, but also that it would pop up more frequently than it does., in local oral traditions.

Meaningful ‘Memories’

Gloria Wekker, a professor of Surinamese descent wrote, apropos of Neus-Van der Putten’s investigation, “It isn’t always easy for someone who has been fed stories of Du Plessis’ cruelty with her mother’s milk to read this [Neus-Van der Putten’s] work.” Wekker’s quote gets to the heart of the matter: the trouble letting go of the deeply-rooted cultural meanings attached to the story of Alida and Susanna du Plessis.

I have spent the last year or so delving into the history of the Dutch Windward islands of St. Maarten, St. Eustatius, and Saba. During my rather extensive exploration of the documentation relating to the history of these islands, I have yet to come across any source that would verify the story of Lohkay. Which has left me in something of a conundrum. So what to do now when the imperatives of empirically-based history would seem to dictate a critical stance towards the reality of these brutal disfigurements? Or now that this same critical viewpoint would seem to cast doubt on the existence of Lohkay entirely?

My recent trip to the Windwards in January of 2016 made clear to me that the memory of Lohkay signals an affective link to the past for many people. In the story of her mutilation, the violent processes of slavery are quite literally incorporated in her body. The emotional resonance of past events is, through her story, made present in the present. The historical memory of these one-breasted women is vital to the means by which people in post-slavery societies grapple with the legacies of gender relations, sexuality, brutality, violence, defiance, agency, and liberation. Ultimately, then, for me, taking a radically empirical stance towards the legends of Lohkay or Alida is meaningless. What would seem to matter in this context is not the past for its own sake, but the relationship between the past and the present.

(Jessica Roitman is a researcher at KITLV working on Caribbean History. Her project, ‘The Dutch Windward Islands: Confronting the Contradictions of Belonging, 1815-2015,’ examines the intersection of migration, governance, and (hybridized) identities on the islands of Saba, St. Maarten, and St. Eustatius.)

No Comments